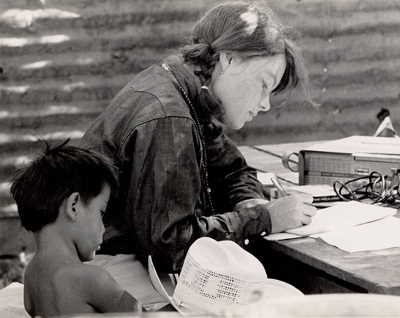

Dedicated students study Seneca at Nation’s Language House

The Seneca Nation Educational Program is trying to bridge this gap by offering open lessons in Seneca every Tuesday and Thursday evening.

“Our doors are open to anyone,” said instructor Marilyn Schindler. “We’re trying to encourage as many Senecas to come down as we can. We try to work around their schedules. Some people have to work all day and can only make it in the evening.”

Along with Schindler, Jessica Huff and others of the Language House teach anywhere from three to eight people each week, free of charge.